Escapism is a fundamental human behaviour as old as time. Storytelling, theatre, cinema, fashion – all have served as portals to somewhere, anywhere, other than here.

Lately, it’s gained prominence in marketing. Burberry has pivoted from fashion photography to cinematic, dreamlike sequences. Soft toy company Jellycat is in Selfridges holding a ‘fish and chips’ store experience with plush toys in place of food and condiments. Nostalgic toys like Labubu and Sonny Angels have gone viral on social media.

It’s no coincidence that escapism in marketing is gaining traction at a time when the world feels… heavy.

Gen Z, in particular, has come of age under the weight of constant crisis: a pandemic, an economic downturn, and a housing market locked behind golden gates. Inflation is up, jobs are scarce, and, for many, financial stability feels a world away. Or, at least online, a scroll away?

We’re turning to our handheld digital panaceas for inspiration, identity and belonging, and seeking a soft-focus fantasy world to smooth the hard edges of real life.

Why is escapism in marketing on the rise?

It’s a sign of the times, amplified by the positive feedback loop of social media.

The more we engage with a certain type of content, the more algorithms feed it back to us. We like it, we see more of it, and creators respond by producing more. Audiences, in effect, co-create trends.

The recent rise of escapism in marketing, then, reflects public sentiment; what we’re engaging with, what resonates. It’s emblematic of our preferences and the political, economic and social contexts that shape them.

At the same time, the more time we spend online (a figure which continues to increase), the more we crave escape from the very thing that’s keeping us there.

Studies show that one in three people wish smartphones were never invented, while 79% of people said they’re actively trying to develop more offline hobbies.

There’s a growing desire to disconnect, but going on TikTok is easier than turning it off.

Immersive commerce as escapism

From the meteoric rise of blind box collectible toys like Labubu to Jellycat’s ever-expanding plush universe, toy companies are central to an escapism economy that is now valued at $9.7 trillion and expected to grow to $13.9 trillion by 2028.

Take British soft toy business Jellycat. Last year, the brand’s ‘fish and chips’ store in Selfridges went viral with queues out the door – and those in line were of all ages. Inside, everything from battered cod to pickled onions is made of plush. Its popularity has sparked a second store set to open in Manchester this year.

@selfridgestoyshoplondon Londons very own Jellycat Fish&Chip shop!🐟 Exclusive to Selfridges #jellycat #jellycatlondon #selfridgeslondon #selfridges #fyp ♬ Cooking, bossa nova, adults, light(950693) - Kids Sound

The surreal Jellycat pop-up is child-friendly, but it also taps into a very adult desire for nostalgic comfort. It’s an example of what has been coined ‘immersive commerce’, where storytelling and spectacle are central to the product.

Labubu leans into ‘trinket culture’

Nearby at Harrods, Pop Mart launched a Labubu pop-up and queues snaked down Brompton Road. What were people there for? A toy bunny with fangs. But also, nostalgia, comfort and a feeling that you have something special.

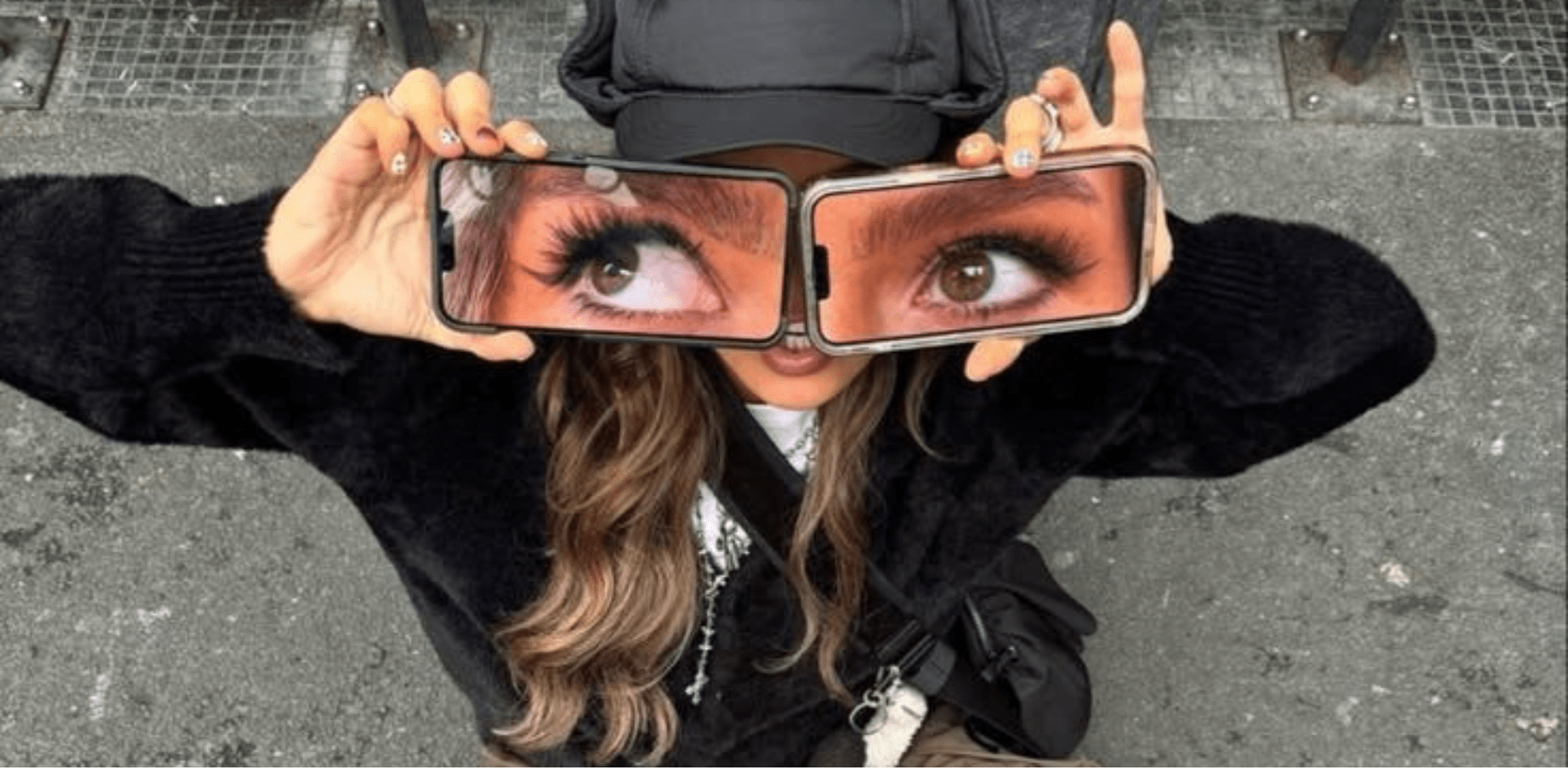

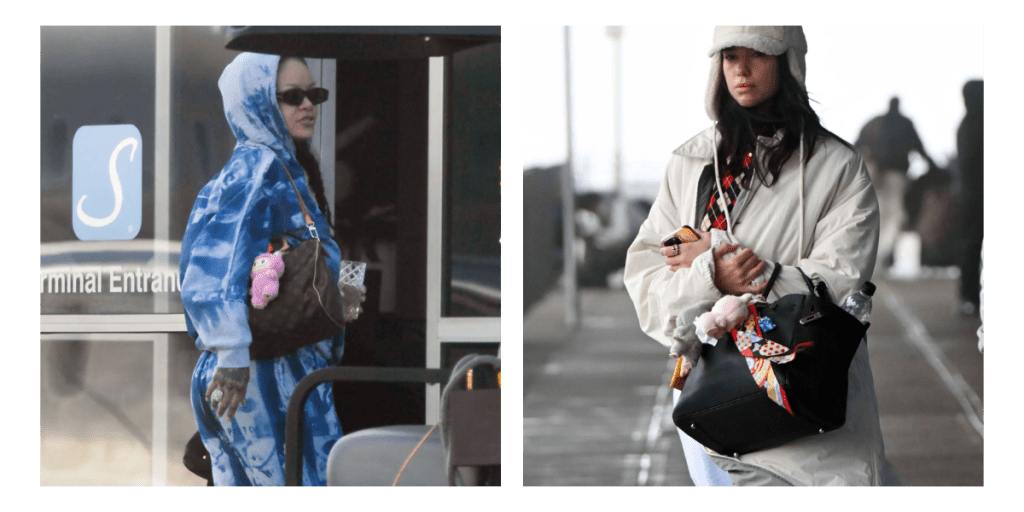

The success of Labubu has also undoubtedly been fuelled by its roster of celebrity fans and scarcity-driven strategy. The toothy toys often sell out in seconds, and resellers command hefty markups online. Now, they’re commonly seen hanging off celebrities’ and influencers’ Birkin bags and have become collectible status symbols.

Labubu’s celebrity fans include Rihanna and Dua Lipa. Credit: theImageDirect.com

The soaring popularity of toys like Labubu, Jellycats and Sonny Angels has coined the term ‘trinket culture’. Aesthetics, after all, are a form of communication, and for Gen Z, these tiny tokens have become identity signals. But some cite the rise of trinket culture as micro-luxuries that are symptomatic of a need for something deeper.

Speaking to Tyla, clinical psychologist Dr Tracy King said: “On the surface, they’re fun and whimsical. But psychologically, they’re deeply symbolic: these objects offer small, accessible moments of comfort, control and identity in an unpredictable world.”

Brand world-building that rivals cinema

As the world grows more chaotic, the appeal of escaping into something weird, wonderful, and above all, safe grows, too.

Brands like Duolingo have thrived in this climate by crafting worlds that intersect with our reality, anchored to the brand through memorable characters and lore.

This strategy, identified as ‘The Script Writer’ in a study by Small World, describes brands whose product isn’t the main source of entertainment. Instead, they build expansive worlds that unfold like a long-running sketch show.

Taking a more literal cinematic leap, Burberry pivoted to short films with its London in Love series earlier this year. Featuring stars like Kate Winslet and Aimee Lou Wood, the series uses storytelling to offer viewers moments away.

If we can’t live the dream, at least we can consume it.

Want to create online and in-person brand experiences that people can’t wait to enter?

We craft bold, earned-media-first ideas and multiply their impact across the full media spectrum, from PR, influencer and experiential to paid media and SEO. It’s all in of our Creativity. Multiplied. philosophy.

About the author

Natalie Clement

With international experience as a digital marketer, writer, and editor, Natalie has worked across sectors including lifestyle, technology, and tourism.